If the recent news of explosions out of Beirut, Xiantao, and Baltimore has made anything clear is that major accidents can happen anywhere and at any time. These events often take weeks to stabilize and years to fully understand. Major accidents often feel random, and we hear phrases like “no one could have seen this coming,” or “we never thought anything like this would happen.” Those phrases are usually from victims or the media. Those of us in the business of conducting major incident investigations understand that failures occur in even the most robust systems. Don’t wait until you are confronted with a major accident and investigation to find out you are not prepared. Companies need to plan for when a disaster occurs to mitigate consequences, save lives, understand what happened, and prevent recurrence.

3 Elements of a Major Incident Investigation

“By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”

– Benjamin Franklin

Being prepared to deal with a major incident starts with a plan. Every good strategy for dealing with a major investigation should have the following three elements:

- Clear Expectations for Coordinating with Emergency Response

- Solid Investigation Policy

- A Systematic Approach to the Investigation

By doing the prep work before a major incident occurs, your team can focus on stabilizing the situation and not miss critical evidence. As anyone who has participated in organized sports will tell you, you won’t be effective at coordinating complex tasks unless you practice them. This means not just having a written policy or plan in place, but performing drills that train the skills needed in an emergency. This can lead to lives saved and avoided injuries by your emergency response crews or investigators.

Safety Stabilizing the Scene Comes First

Major incident investigations often begin before the situation is stabilized. Therefore, it is essential to consider not just does your team have the skills necessary to conduct the major incident investigation, but that they also safely get on-site to secure evidence and information. There are a few acronyms that are used for first response techniques. In our training we discuss, “SAY”, “ESPN” and “RESPOND.” These techniques first focus on understanding the safety requirements of a scene before focusing on collecting evidence. Whatever acronyms or techniques you push should be known and practiced by your investigators.

Knowing is Half the Battle: Build a Solid Major Investigation Policy

The easiest way to know you are not ready for a major incident investigation is if you don’t have an investigation policy. Your policy should focus on two things:

- It should detail what types of problems should be reported/investigated

- It should provide guidance on how root cause analysis (RCA) should be performed for the different levels of risk

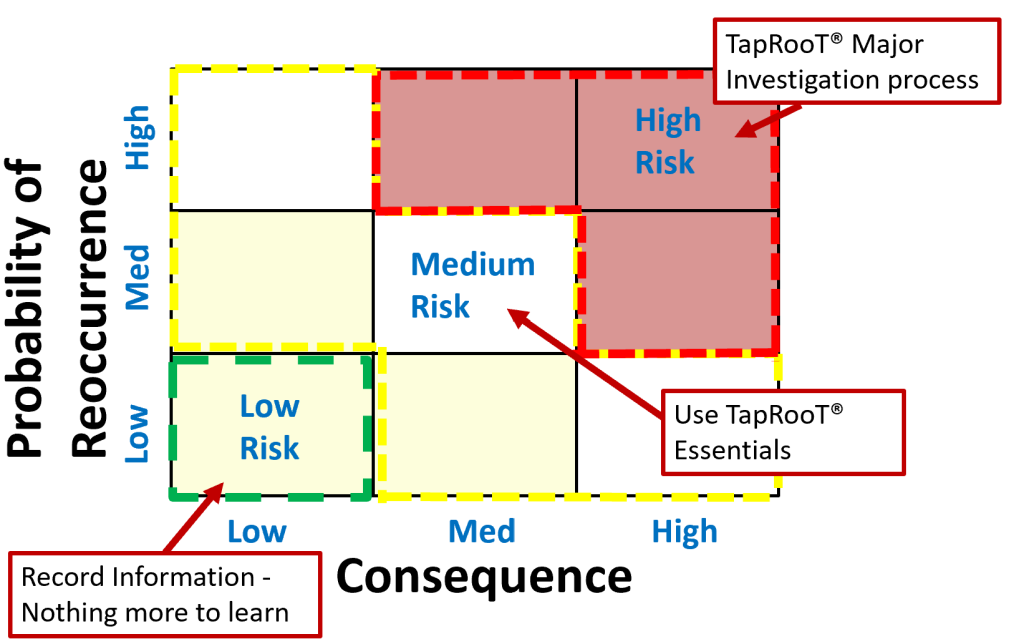

The image below gives an example of how you could go about guiding investigators on what techniques to use given probability vs. consequence:

A Systematic Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Process Removes the Guesswork

“Major accidents aren’t caused by simple, easy-to-fix problems. You must discover the causes of perhaps complex, difficult to solve problems, develop effective fixes, and then present what you have learned to management in such a clear, unambiguous way that they understand the problems and the solutions. Management must leave the meeting convinced that they need to change the way they are managing the company and lead the change that needs to happen.”

– Mark Paradies

Using TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis for Major Investigations

An organized process is needed to meet management’s or the public’s expectations for answers after a major incident – a process that not only explains what happened but how investigators came to their understanding of what happened.

A systematic approach to root cause analysis should allow you to understand:

- What happened

- Why it happened

- Help with the development of corrective actions

- Deliver repeatable results

If you use a process that isn’t repeatable, you may often find that management will come to a different conclusion than the investigators. For this very reason, a non-systematic RCA process often prolongs major incident investigations and can lead to investigators missing critical details or answers.

Major Accidents are Hard to Think About

No one wants to picture having a major accident at their facility. Few want to even think about the possibility of a major accident happening. However, denying the possibility, even if you feel it’s remote, can leave your employees and company more vulnerable to risk. The actions investigators take after a major accident occurs can either contribute to the damage or mitigate the damage. Preparing in advance is a time well spent for the good of all.

Learn More

Better investigations are the first step to uncovering the root cause of incidents and preventing serious injuries, fatalities, and major accidents.

To learn more, check out the following helpful resources: